Read below as this Q&A dives deep into drug addictions and Boyce’s reasoning for writing this memoir.

What made you want to write a book about the war on drugs?

I am an addicted person myself, and even though I have carried that identity since I was a kid, even I truly believed being addicted meant exactly what the world told me it meant. I thought I was a bad person, a sinner, a weak crutch-user who would never reach my full potential until I stopped using drugs. It took me a lot of time and a lot more luck to discover we have all been lied to about drugs and those who use them. That knowledge allowed me to succeed in ways I never dreamed possible, and I realized I had to share it when people close to me continued to die because of the war against drug users—a war that is fueled exclusively by the lies I myself believed for so long.

What’s the fundamental problem with the war on drugs?

The fact that we can even think about our drug problem in terms of war reveals the depth of our self-deception. We pretend to think addiction is a disease (which it is not), but then we offer nothing resembling treatment. Instead, we lock people up, raid their homes, take their property and sell it at auction, put their kids in foster care and ruin their lives; this is not treated, and that is because we have never really thought addiction was a disease (which it is not). But it is a health problem, and you can’t defeat a health problem with war; war is a health problem. Unfortunately, in the United States, war is often the only solution we understand to a complicated problem.

What was it that prompted you to think that the war on drugs was the wrong direction for society to take?

As an addicted person, this is personal for me. I have lost friends and family members to this war, and as soon as I became an addicted person myself, it was immediately obvious what the war was really about: money. We drug users and addicted people don’t need punishment or discipline. We need love and healing. But since we fuel a massive industry of treatment, incarceration, and parole/probation, we become ensnared by a system that requires us as fuel. Medication was the only way I got through the therapy I needed to get back to living, and without it, I would have just continued to take heroin, the only thing that made life worth living.

Why do people use drugs like cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine?

That question is more complicated than it sounds. There is a single answer, but there are also three very distinct answers because different drugs do different things in the body. The single answer is that people enjoy the way these chemicals make them feel. But the more complicated answer is also the more interesting, at least in my mind.

Drugs like heroin, along with benzodiazepines and barbiturates and, to some degree, alcohol, are best thought of as drugs of the feast. They activate the same neural circuits as a feast, or a completed task, or a satisfied sigh, and when we use them we find ourselves fulfilled in that very-human way that usually requires a lot of work. But we can skip all the cooking, chewing, and digesting and, instead, just take a drug of the feast and find that human space of satisfaction.

Drugs like methamphetamine and cocaine, on the other hand, are best thought of as drugs of the hunt. They activate the same neural circuits as a hunt, a challenge, or a task we are dedicated to completing. Again, hunts or puzzles or complicated tasks are, well, complicated, and as much as we humans enjoy them for the thrill they give us, we also enjoy just skipping the task and taking the shortcut. Different drugs do different things in the body.

Depending on the length of time you want to dedicate to each hunt, and sometimes how much cash you have to throw at the situation, drugs like methamphetamine or cocaine are situational choices. That is the three-part answer.

How would legalizing or decriminalizing all drugs benefit our society?

Addiction takes many forms and stems from many causing factors, but one of the biggest is trauma (some 75% of people who struggle with addiction report childhood trauma—more depending on the study). The worst thing we can do for someone who is struggling with addiction is to traumatize them further. Yet we continue to throw people in jail for using drugs or committing crimes related to addictions, even though we know that jail increases the risk of overdose many times over shortly after release, and it has never been shown to reduce the use of addicted people who don’t want to stop using.

We should also not forget that 80% of people that try even the most socially stigmatized drugs—things like crack cocaine, heroin, or methamphetamine—80% of those folks will never struggle with addiction in their lifetime. f you are one of these people in the majority, a user who does not struggle with addiction, then you should be allowed to access a safe, legal supply without worrying about a robbery, adulteration, or overdose.

Your book not only tackles the war on drugs from a scientific level but also from a personal one. What inspired you to incorporate your own stories?

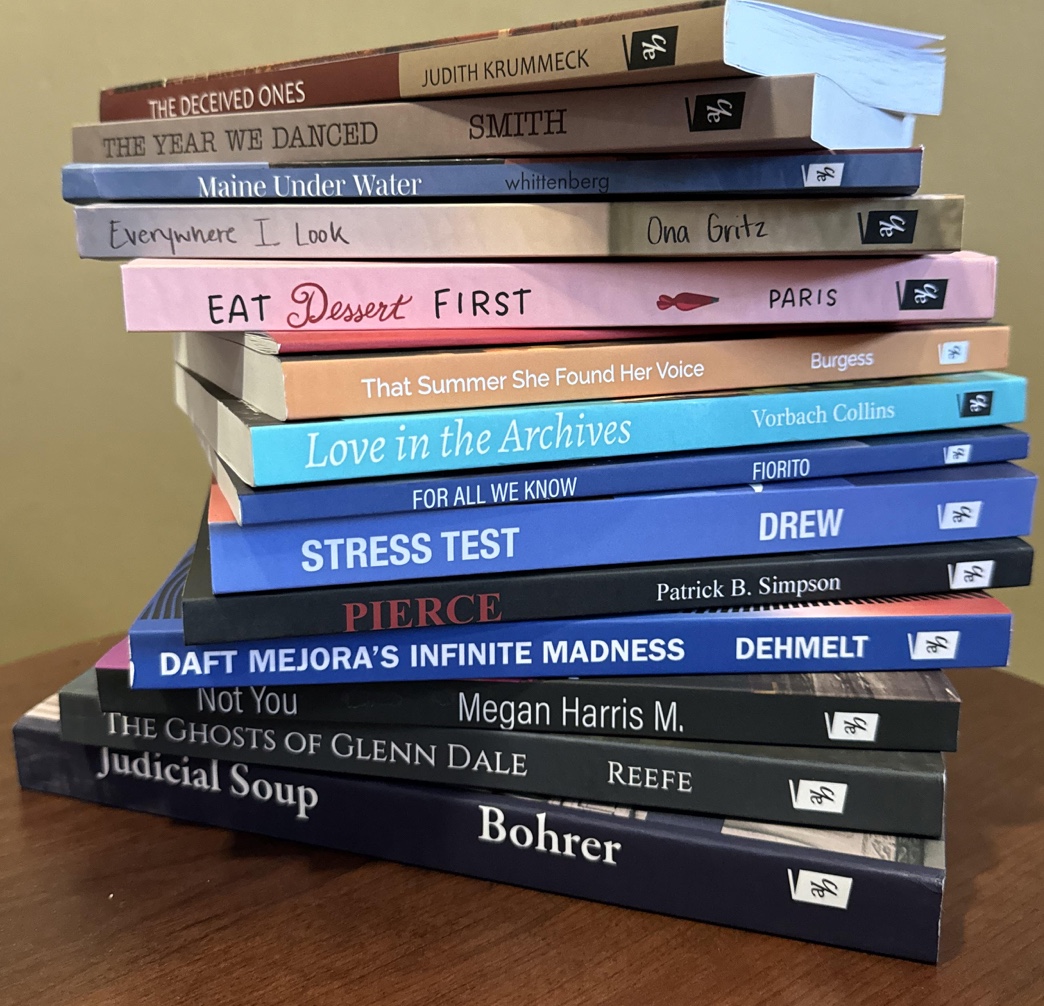

There is a long history of using one’s personal story to make the connections clear, so I am following my heroes like Maia Szalavitz’s, who wrote Unbroken Brain, and Carl Hart who wrote High Price, not to mention Razor Smith, David Poses, Sam Harris, Ted Conover, and untold others. But more than anything, these stories needed to get out, and my own experiences with drugs often seemed to be the best way to make my point. Humans learn by association. When we can connect an abstract idea to flesh and blood, we are more likely to understand the issue.

Did you find it more difficult telling the stories of your personal experiences or expanding upon the scientific aspect of the war on drugs in our society?

The oddest thing about writing this book was how easy it was to find the scientific data regarding drugs despite the fact that it was largely contrary to what I had been taught growing up. These are not hidden studies or darknet blogs; they are scientific journals that are easy to find. But despite that, I had a hard time incorporating these ideas into my preconceived beliefs, because humans are really good at holding on to bad information from our past even when we know better. I talk about this in the book quite a bit, and it is kind of ironic that the book itself came from a place of hard learning.

Why is it important to think about set and setting in our daily lives, especially when using drugs?

Set is what is going on inside your body: your past, genetics, biology, and state of mind. If you are angry, depressed, manic, hungry, horny, or discontent, your drugs will affect you in ways that might not otherwise affect you on a different day, in a different mood. Setting refers to the place where you use your drugs and the people who are there with you. If you use a drug around an anxious person, or outside the police station, you will probably have a very different experience than if you use it at home or in a safe space.

Ignoring the importance of set and setting can actually prove deadly. Our bodies have evolved to recognize signs in our environment, and to adjust our biochemistry to allow for more of things we enjoy (and, conversely, less of things we do not enjoy). With heroin and other opioids, we notice things in our environment that cue our subconscious to the fact that we are about to use (smells, sounds, sights, tastes, time-of-day, rooms we are in, etc.), and somewhat- automatic adjustments allow for the administration of more than we might otherwise be able to handle if our bodies didn’t know it was coming. But when we are not in our normal environment, those clues don’t appear, or they don’t work as well as they otherwise would. In rat experiments, doing something as simple as changing the color of a box where the rat normally uses heroin or cocaine was enough to make them overdose on quantities of the drugs they had taken dozens of times before with no issue.

What solutions can you offer on a personal level?

Know thyself. It sounds cliché, I know, but it is a deep statement. Know what makes you tick, what makes you blow up, what makes you want to live, and what makes you want to die. Know what drugs work for you and which you should avoid, and then figure out which tools work for you and which aren’t worth the effort. Life is about navigating, rethinking, and finding better pathways to the same location. Keep getting better, and don’t allow anyone else to define “recovery,” or “success” for you. Your success will look different than the success of others, and that is okay.

What solutions can you offer on a social level?

This is where the majority of our work needs to take place. We need to move from a focus on punishment to a focus on prevention. Culturally, we don’t debate whether or not we should chase down tornados and punish them, or whether we ought to unleash our vengeful anger on the cliff-edge our loved one fell from. There is no intent in our mental models of the world, and so we don’t’ feel the desire to mete out retribution. But neurology and psychology are currently dragging spirituality kicking and screaming to the conclusion that free will is not what we have always thought it to be. We can all imagine plenty of ways a child could be easily “programmed” by pain, torture or simple brainwashing to perform what amount to awful acts on others, and we wouldn’t blame the child. But our refusal to focus on the causation instead of retribution when it comes to criminality stems from our refusal to drop the illusion of free will. We can prevent crime, but never by punishing it after the fact. We can continue to spend $40,000-per-year-per-inmate on revenge-focused strategies of punishment, or we can get to work disassembling the prison-industrial complex by emptying it out and leaving it obsolete.