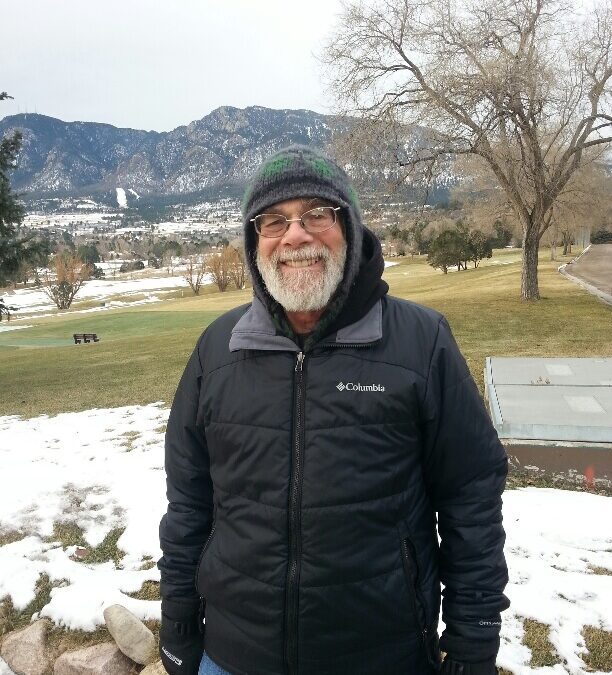

Read our Q&A with Robert Cooperman to understand the meaning and inspiration behind his lovely collection of basketball poems.

- Who do you hope reads Go Play Outside? Do you have one specific target audience or multiple?

Anyone who loves and reads contemporary poetry and incidentally, anyone who loves or plays or used to play basketball. But ultimately the only real target audience for me is me. If I don’t like what I’ve written, I doubt anyone else will. I write for me, for my loves and obsessions. I’m surprised I haven’t written a collection about my favorite movie as a kid, Spartacus, which had me in tears when I was 13 or so and sat through it twice in one afternoon.

- When did you realize you had poetry inside of you? Furthermore, what do you get out of writing poetry as opposed to other styles of writing?

I wrote all kinds of verse as a little kid but didn’t realize I could make it my life’s passion until a friend at work (at a sleazy publisher in Manhattan) told me there are graduate programs in Creative Writing. I’d showed him some poems and he’d been very supportive. He was a wonderful guy, John Burnett Payne.

Since I write poetry almost exclusively, to me, when a poem works, when I nail the closure, it’s a real rush, like I’m walking on air, like I could dunk a basketball, if I weren’t old, slow vertically challenged, and didn’t have my feet nailed to the floor.

- What makes the stories behind this collection of poems meaningful to you and worth sharing with others?

Go Play Outside is about my first love, or passion, or obsession, basketball. Like a lot of other kids in NYC, I used to be able to tell you the name and college of every single NBA player. Also, basketball is very much a city game, game immigrants picked up on very quickly, and since I’m both originally a city kid and the grandson of immigrants, the game had a special appeal to me. Plus, it’s also a gateway into American culture. There’s always a court, or at least a hoop, somewhere, in any city and town in the country. When I was traveling in Europe, I came across a b-ball court in Amsterdam and started shooting around with another guy, who turned out to have grown up just a few blocks from where I came up. A small world made smaller.

- If you were a reader buying your Go Play Outside, what would you hope the takeaway to be? How would you want to feel?

I’d like to read competent poetry that tells compelling stories. By the end, despite the ultimate sadness of the final section, I’d want to feel elation to be taken into a world I might not be as familiar with as I thought I was. I’d want my world opened up a bit. We don’t just read to have our realities confirmed, but to see other worlds, other points of view.

- What was your main inspiration for writing Go Play Outside?

To be quite blunt about it, I had some poems lying around about basketball; they’d been accepted in various magazines, and I was looking for a new, big project, so I started writing more poems about basketball until I had enough for a full manuscript. It was also a chance to re-connect with my youth and young adulthood, and what I love and couldn’t do anymore, owing to total hip replacement surgery. This was a way to vicariously play the game again.

- How did you feel once you completed Go Play Outside?

I felt elated. I knew I’d written a good, tight, coherent collection, even if no one else was going to read it.

- Why did you choose this specific title?

The title just sounded good to me, catchy. Plus, it’s an accurate depiction of how I feel about things: the two pulls, one to get out and do something, and the other to sit in a quiet corner and read.

- What was the most challenging aspect of writing Go Play Outside?

It wasn’t challenging at all. It just flowed. Well, challenging in sometimes having to create names for people I knew who may not have wanted their real names bruited around. But as Keats said, “If poetry doesn’t come like leaves to a tree, it best not come at all.”

- What other books have inspired your own writing? Do you have any particular authors whose writing style/approach has impacted your own?

Two huge influences, though you can’t tell by this book, were the 18th-century novelist Tobias Smollett, in his novel Humphrey Clinker, and the other was great Victorian poet, Robert Browning because both employed multiple points of view. I’ve written several collections based on Greek myths and also retellings of Old West characters, and you can see that shifting point of view in those collections.

- Do you have a specific part/poem in Go Play Outside that is your favorite? If so, why?

I’d have to say the last section of the book is my favorite because it deals with my all-time sports idol, Elgin Baylor. He was my childhood hook into the game. My dad called me into the living room one Sunday afternoon, to watch a game, and pointed to the screen, “Look at this guy, there’s never been anyone like him.” I was addicted. Strangely, sadly, a friend called me one recent morning to give me the bad news that Baylor had died. I was devastated. Then a few hours later I got an email from Apprentice House that the collection had been accepted, so I had very mixed feelings. I then tacked on one last poem, about Baylor’s death, to the collection.

- How did the sport of basketball and you own personal relationship with the game inspire you to write Go Play Outside? Furthermore, how did your upbringing and your childhood and young adult years impact the book?

It seemed like a natural. I’d written about other aspects of my life: my dad’s failed hat business, my battle with the local draft board during the Vietnam War, my parents’ stay at Ft. Bragg at the end of WWII. So, it seemed inevitable to write about my first love. My dad was a terrific athlete; he played semi-pro baseball, boxed, and played basketball as a kid, oh and he was also a whiz at handball, the city sport before basketball. My younger brother is also an excellent athlete, a natural, as they say, and a lot bigger than me. Me? I had all the aspiration to play the game but realized pretty early I was mediocre, on my best days. But all through high school and college, Friday afternoons were devoted to playing b-ball. Same in grad school, when I moved to Denver. My wife jokes that her first glimpse of me, in a poetry workshop, was me walking in with my basketball since some of us were going to play after the weekly three hours of humiliation by the Poetry Coach.

- What advice would you give to new authors who are looking to have their work published?

First, before you even think about getting published, learn your craft, and even before that, read your elders and betters: the Immortals, like Shakespeare, Keats, Wordsworth, Eliot, Yeats, Frost, to name just a few. And the poets who mattered in the generation before ours: Merwin, Hall, Sexton, Plath, William Meredith, to name another few. I’d also tell them to learn all they can about prosody, even if they never write a formal poem. Adhering to rhyme and meter is, if anything else, great practice. The late Richard Wilbur was a master of form; Rhina Espaillat is also a fabulous formal poet. Seamless. And finally, I’ll give the advice that was given to me: when you send work out, start at the top, even if it means banging your head against a wall of rejections. Don’t be discouraged by rejections; even Theodore Roethke’s work was rejected toward the latter part of his career.

- In looking back at your writing career over the years, how have you progressed as an author? Is the writing process different, easier, or perhaps challenging in ways that are different from when you first started out?

I’d like to think I’ve gotten better as a poet, that I’m more careful, don’t rush things, don’t settle as much. The only thing that’s changed about my writing process is that I no longer (unless we’re traveling) write the first draft longhand. Everything goes on the computer. This came about by lazy necessity: during one terrible heat wave fifteen years ago, it was too hot for me to even think about moving my writing to my typing desk. So, I just switched to the keyboard. Besides, my handwriting is so horrible I couldn’t read half of what I’d written if I let it sit for a day or so. If I’m on a project that really holds my interest, then the poems, as always flow. If it’s something I’m sort of indifferent about, then it’s like pulling teeth, but strangely the poems I view as most successful are often the ones that had the hardest birth process. I love to fight a poem, to get what I mean and say where it’s meant to go.